Not sure what I was thinking when I wrote this poem. Apart from the last two lines of each verse it begins in a form of prose and ends up a rhyming poem. Oh well, who’s to judge?

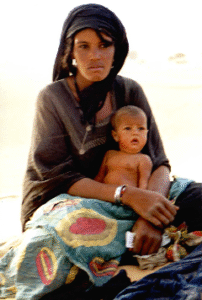

One thing I do know. They are lovely people. One woman came over to me. She lay a blue cloth on the sand and on it, she placed a few articles of jewelry, that she had made. She sat on one side of the cloth with her baby in her arms and invited me to sit opposite her. I had learnt how to say “How much?” in Tamashek, her language, and she replied by displaying her hands and fingers. We sat for a while in silence, just gazing at each other, talking without words. I gave her an energy bar of seeds and raisins that I had brought from home. She smiled and tucked it away in her tunic for later.

Tuareg Lady

In the harsh desert conditions

of the Aïr mountains,

where no man meets a nomad,

life…

and death…

appear from no where.

In the Aïr.

And the life

that appears

is often a young lass

and her child.

Her husband –

on the move,

in a caravan,

so far away.

That’s their way.

You stop your truck

to fetch wood

for the evening camp fire,

after so many hours

of lone travel,

along the Piste,

and you think that no-one else exists.

And then she comes,

unannounced, no song, no drums.

She stands,

proud,

with her child on her arm,

a little to one side,

and waits.

This is not the oppression

of a creature lower than man.

This is respect,

and protocol.

For she will be greeted

and asked,

what she might need:

the Tuareg breed.

And the handshake –

a ritual

of minutes.

A symbol of caring,

sharing,

respect,

and the love

of a heaven above.

After the greetings

she may smile

and look down,

coy.

Hahmdi,

our leader,

would ask how her children are

and she would say

what was on her mind

and what she really did need,

without any greed.

For her existence

was meager.

Yet,

as long as there was no drought

she was never without.

But without is a relative word.

For what she had

would, for you and I,

be poverty,

disaster,

even disgrace.

Yet her life is fulfilled,

natural,

and free.

Not like you and me.

She would never beg,

never steal,

but would accept

what we had,

to offer.

She would not ask

but would point out her need,

starting with her child…

and its health…

nothing to do with wealth.

Perhaps the baby’s eyes were sore,

or a rash on his arm,

or a gash on its leg.

Medicine would be gratefully accepted

and no more asked.

And, if it should chance,

that we do not have the right cure

she would accept with a smile –

a sight worth while.

For, when our caring is done,

before we say goodbye

I see her face.

almost white

with the style and pride of the Berber

in the north.

She is a beauty,

with skin so pure,

and a stance that is sure.

Her presence

fills the desert

and her charm says:

this is my life,

for I am the wife

of a Touareg nomad

and he is on his way,

home.

This is how we live

and God we forgive.

Even though our age

averages out to fifty

because of the many children

that die.

We never ask why.

For we are proud:

as erect as I stand

on this marvelous land.

I have no fears

and never count the years.

Life is as it comes

and when God beats his drums

it will rain

then once again

my Korry will bring water

and my daughter

will have a chance to survive,

to stay alive.

And the valley will explode

into a fertile road

where we will come and go,

where my children can grow.

And when it dries

from the baking skies

that’s just Allah’s way

and we must pray

our thanks to the one

that provided the sun

that shines on our land

which is forever grand,

noble and pure

and, to be sure,

we Touareg

would never beg

to be in any other place

nor to be another race.

And, as she walks away,

I know I’ll never forget the day,

that I met a lady of Aïr

who showed me how to care

for the real things in life.

Why do we make such strife?

Copyright © 01.06.1998 – Kevin Mahoney